his

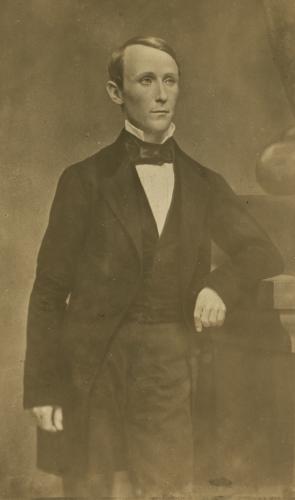

William Walker, ca. 1855–1860, by Mathew Brady (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

On

November 8, 1855, on the central plaza of the Nicaraguan city of

Granada, a line of riflemen shot General Ponciano Corral, the senior

general of the Conservative government. Curiously, the members of the

firing squad hailed from the United States. So did the man who had

ordered the execution.

His name was William Walker. Though later generations would largely

forget him, in the 1850s he obsessed the American public. To many, he

was a swashbuckling champion of Manifest Destiny. To others, he loomed

as an international criminal. In Walker’s own mind, he was a conqueror

destined to create a Central American empire. His bizarre career would

leave a legacy that shadows the relationship between the United States

and Central America to this day.

William Walker, ca. 1855–1860, by Mathew Brady (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

On

November 8, 1855, on the central plaza of the Nicaraguan city of

Granada, a line of riflemen shot General Ponciano Corral, the senior

general of the Conservative government. Curiously, the members of the

firing squad hailed from the United States. So did the man who had

ordered the execution.

His name was William Walker. Though later generations would largely

forget him, in the 1850s he obsessed the American public. To many, he

was a swashbuckling champion of Manifest Destiny. To others, he loomed

as an international criminal. In Walker’s own mind, he was a conqueror

destined to create a Central American empire. His bizarre career would

leave a legacy that shadows the relationship between the United States

and Central America to this day.

Soon after his birth in Nashville in 1824, Walker began to manifest unusual intelligence. A gifted student, he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a medical degree in 1843, before he turned twenty. He was also restless. He began to wander the globe, from Europe to New Orleans. In the latter city he turned to journalism, editing the New Orleans Crescent.

“He listens to everything in a quiet way, says but little, speaks in a mild and subdued tone, and has rather the appearance and manner of a clerical gentleman,” Commodore Hiram Paulding later wrote. Walker was a small and slender man, with freckles, gray eyes, and thinning hair. “He is said to be remarkable for his abstinence,” Paulding added, “and that wine and the society of ladies have no charm for him.” But these observations did not quite describe Walker during his residence in New Orleans, for there he had a brief relationship with a deaf and mute woman named Ellen Martin. In 1849, she died of cholera, a tragedy that propelled him to San Francisco.

The move turned Walker’s life in a radical new direction. The Gold Rush was in its early stages, attracting tens of thousands to California. The Forty-niners were an independent lot, willing to hazard the long, dangerous journey from the settled states. Duels, gunfights, and brawls erupted regularly.

And there was more to this historical moment than the Gold Rush. Over the previous decade, the United States had expanded deep into Latin American territory, and not always through federal action. Americans in Texas had rebelled against Mexico, established their independence, and won annexation to the United States in 1845. The Mexican War broke out in 1846, leading to the absorption of a third of Mexico—with the assistance of American citizens in California, who staged their own revolt against Mexico.

Enthusiasm for geographical growth came to be known by the newspaper slogan of “manifest destiny,” but it reflected mixed motives. Some Southerners hoped to extend the territory open to slavery. Others felt an evangelical fervor for exporting democracy and Protestantism to the military regimes of Catholic Latin America.

This aggressive expansionism gave rise to a strange phenomenon known as filibustering. Filibusters were independent adventurers who launched freelance invasions of foreign countries, usually aiming to annex them to the United States. The decade before the Civil War saw the great flowering of filibustering. In 1850 and 1851, for example, scores of Americans landed in Cuba in disastrous forays.

The restless Walker decided to become the greatest filibuster of them all. In 1853, he invaded Mexico with a handful of men, and barely escaped alive. The United States government tried him for violating the neutrality act, which prohibited private citizens from warring against foreign nations. But a jury in turbulent San Francisco swiftly exonerated him, turning his failure into a personal (if not military) triumph.

In 1855, he found his next target: Nicaragua. But this time his expedition would be conducted in cooperation with local forces. In its less than two decades of full independence, Nicaragua had suffered from repeated civil wars, waged by the leaders of its two main cities, León and Granada—capitals respectively of the Liberal and Conservative Parties. When the Liberals rose in yet another revolt, Byron Cole, a friend of Walker’s, negotiated a contract for Walker to fight on their side.

Why did Walker care about poor and distant Nicaragua? It was home to one of the key “transit routes” between California and the rest of the United States. Before the construction of the transcontinental railroad and the Panama Canal, most travel and almost all commerce between the two coasts went by steamship to Central America, where two routes crossed the isthmus. The first was in Panama, spanned by the Panama Railroad. The other was in Nicaragua.

In 1851, Cornelius Vanderbilt (known to all as the Commodore) had established the Accessory Transit Company to span Nicaragua and connect to his steamships. The company ran riverboats from the Atlantic port of Greytown, up the San Juan River to Lake Nicaragua. From the lake’s western shore, a twelve-mile carriage road descended to the Pacific port of San Juan del Sur. Accessory Transit carried tens of thousands of passengers each year, making Nicaragua a strategic priority for the federal government. As President James Buchanan later said, “To the United States these routes are of incalculable importance as a means of communication between their Atlantic and Pacific possessions.”

On May 4, 1855, Walker slipped out of San Francisco Bay in the brig Vesta, along with fifty-seven followers (one of whom died at sea). Though he spoke little Spanish, he demanded an independent command when he arrived in Nicaragua. He promptly launched a blundering attack, and was lucky to survive.

But luck was his foremost attribute. The Liberals’ chief executive and commanding general both died soon after his arrival, making him the senior leader on his side. Then Walker carried out perhaps the only inspired maneuver of his career. He commandeered an Accessory Transit steamboat, landed his men in the rear of Granada, and captured the city. He then took hostage the families of the Conservative leaders.

General Corral quickly agreed to terms. Walker, seeking to consolidate his power in the small country, created a unity provisional government, with the weak Patricio Rivas as president, himself as commander of the army, and Corral as secretary of war. Shortly afterward, Walker put Corral on trial for treason and had him publicly executed. The freckle-faced filibuster had made himself into Nicaragua’s strongman.

He would be hard-pressed to remain in power. The neighboring republics, alarmed by his success, prepared for war. And he could not rely on Nicaraguans to fight for him. As he later wrote, “Internal order as well as freedom from foreign invasion depended . . . entirely on the rapid arrival of some hundreds of Americans.” And that made him dependent upon the steamships of the Accessory Transit Company.

Before leaving San Francisco, he had called upon Cornelius K. Garrison, Accessory Transit’s agent there, to ask for passage for himself and his men. Garrison refused. Later, when an Accessory Transit official in Nicaragua donated $20,000 in company gold to Walker’s regime, Garrison fired him immediately.

But Garrison could not remain aloof forever. One of Walker’s closest friends was about to embroil Garrison, and some of the most prominent businessmen in America, in a private war over Walker’s very survival.

That friend’s name was Edmund Randolph, grandson of a Founding Father and a leading attorney in San Francisco. After Walker’s triumph, Randolph paid a visit to Garrison. He explained that he would soon convince Walker to revoke the charter of the Accessory Transit Company (which was a Nicaraguan corporation). Randolph freely admitted that he wanted “a grant for myself of a charter of a similar nature.” He had no steamships, but no matter; he intended to profit by flipping the transit grant, selling it to Garrison as an individual entrepreneur.

Garrison indignantly refused to take part. His partner, Charles Morgan, was the foremost man in Accessory Transit in New York; he could not afford to betray him, even if he was willing to. But Randolph’s certainty about the company’s demise gave him pause. “If things should take that twine,” Randolph recalled him musing, “he did not wish to be involved in the ruin. . . . He would do nothing whatever against the company, but if they fell wanted to save himself.”

The wily Garrison saw a way to save himself, and Morgan as well. He sent his son to Nicaragua, along with Randolph, to negotiate with Walker over the terms for a new line. Once his son reached an agreement, he was to sail for New York to bring Morgan into the plot before it became public knowledge and Accessory Transit shares collapsed in the stock market.

Walker agreed to Randolph’s plan, and the two soon made a deal with Garrison’s son. Morgan and Garrison would pay Randolph for the transit rights and start a new steamship and transit line. Walker would seize the Accessory Transit riverboats and domestic infrastructure, and give them to the two partners. The new line would carry filibuster recruits from the United States for free, accumulating credits toward the cost of the property in Nicaragua. Garrison’s son rushed to New York to explain the arrangement to Morgan.

As luck would have it, at that very moment Morgan was being pushed out of Accessory Transit by Cornelius Vanderbilt. The two had battled over the company for almost three years; Vanderbilt had departed from its management, but at the end of 1855 he began to buy control of its stock. So Morgan readily agreed to Randolph’s plan, and secretly prepared to start the new Nicaragua line.

News of Walker’s revocation of the Accessory Transit charter hit Wall Street like a “bombshell,” the press reported. Vanderbilt rushed to Washington to secure federal aid, but the Cabinet, like the nation itself, was divided over whether Walker was a criminal or a hero. So the Commodore sent a subordinate to retake the company’s steamboats on the San Juan River. He counted on support from the British, who were hostile to filibustering and claimed a protectorate over the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua. The Royal Navy stationed warships in the harbor of Greytown, the little port at the mouth of the San Juan.

But the former Accessory Transit agent in charge of the boats refused to hand over them over, and the British declined to intervene. It was a fateful failure. Had Vanderbilt’s man succeeded, Morgan and Garrison could not have opened their line, and Walker would have been cut off. Instead, Central America descended into war.

In April 1856, Costa Rica launched an invasion of Nicaragua, occupying the city of Rivas. Walker launched a typical frontal assault and was soundly defeated. But his luck held: a cholera outbreak forced the Costa Ricans to retreat, even as Walker gained hundreds of recruits carried by Garrison and Morgan’s new line.

But Walker’s arrogance alienated even his own puppet president, Patricio Rivas, who suddenly denounced him as an usurper and fled over the border. A northern alliance, consisting of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, marched into Nicaragua, occupying León on July 12. Walker responded by staging a rigged election that made him president. He declared English to be the official language, and issued an edict legalizing slavery. Then the Costa Ricans invaded again from the south.

Walker knew he could survive only if he kept open the flow of reinforcements from the United States. As he later wrote, “It was all-important to keep the transit clear.” So he decided to withdraw to the south and garrison the transit route, from Rivas in the west to forts along the San Juan River. He evacuated Granada, leaving a detachment with orders to burn the city to the ground. When the filibusters finished, they erected a sign that read, “Aqui fue Granada”—“Here was Granada.”

By the end of 1856, Walker felt reassured. “Walker, keeping his forces concentrated, can maintain himself in Rivas,” an American naval officer reported. “If the external aids he has hitherto relied upon do not fail him, he will repel his enemies.”

At that moment, Vanderbilt was moving to cut Walker off from his “external aids.” Walker’s greatest vulnerability, he believed, remained the steamboats on the San Juan River. If Vanderbilt’s agents could seize them, he would force Garrison and Morgan to halt operations and cut off Walker’s flow of reinforcements. This time he negotiated an alliance with Costa Rica. In October 1856, he dispatched a special agent to San José, the Costa Rican capital. The agent, a New Yorker named Sylvanus Spencer, had worked on the San Juan River, which gave him precious knowledge of the steamboat operations.

Spencer arrived in San José with Vanderbilt’s plan of attack and $40,000 in gold to pay Costa Rica’s expenses. President Juan Rafael Mora put him in charge of a commando force. Spencer led the men through the rain forest to the San Juan River, where they captured a filibuster strongpoint and a few steamboats. Then he used his knowledge to bloodlessly seize the rest of the boats and forts—sailing up in a captured steamer, giving the right signals, then surprising the filibusters with soldiers who had been hiding on deck. Within days, Spencer controlled the river. Morgan and Garrison, unable to send passengers and reinforcements across Nicaragua, immediately withdrew their ships. Walker was isolated.

Walker withdrew into Rivas, where the Central American alliance besieged him for months. Finally, on May 1, 1857, he surrendered to an American naval officer, who conducted him and his men out of the country.

In some respects, Vanderbilt’s victory was hollow. Though he inflicted heavy financial losses on Garrison and Morgan, he failed to reopen the transit route. The Nicaraguans could not bring themselves to allow large numbers of North Americans into the country again, lest they face Walker once more.

“That man has done more injury to the commercial & political interests of the United States than any man living,” wrote President Buchanan. But the federal government proved ineffectual in either convicting Walker in court, or in preventing further expeditions. Wherever Walker went in the United States, he was greeted by throngs of admirers.

And so he tried again, and again. On November 25, 1857, he landed at Greytown with 270 followers; in a controversial move, the US Navy forced his prompt surrender. Walker launched a final invasion in 1860. But now his luck ran out. The Royal Navy captured him, then handed him over to the nearest authorities, the Hondurans. On September 12, 1860, Walker faced his own firing squad.

Within a year, the United States plunged into the Civil War. Places with names like Antietam, Shiloh, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness soon obscured Granada, Rivas, and Greytown in the American imagination. Memories of the filibuster faded. But Walker himself had contributed to—or reflected—the nation’s descent into war. He had emerged out of a rising tide of freelance violence; and he had appealed to Southern hopes for expanding slavery by reinstituting it in Nicaragua.

Though he has been largely forgotten in the United States, he is still remembered by Central Americans, who see him as a symbol of imperialism. The fight to eject Walker forms part of Nicaragua’s national legend, a critical period in the formation of its national identity.

If nothing else, his disruption of a critical route to California, his military dictatorship, and his ruthless violence—particularly his wanton destruction of Grenada, one of the oldest cities in the western hemisphere—prove that he was one of the most dangerous international criminals of the nineteenth century, if not all our history.

T. J. Stiles is the author of The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (2009), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, and Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War (2002).

The Filibuster King: The Strange Career of William Walker, the Most Dangerous International Criminal of the Nineteenth Century

William Walker, ca. 1855–1860, by Mathew Brady (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

William Walker, ca. 1855–1860, by Mathew Brady (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)Soon after his birth in Nashville in 1824, Walker began to manifest unusual intelligence. A gifted student, he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a medical degree in 1843, before he turned twenty. He was also restless. He began to wander the globe, from Europe to New Orleans. In the latter city he turned to journalism, editing the New Orleans Crescent.

“He listens to everything in a quiet way, says but little, speaks in a mild and subdued tone, and has rather the appearance and manner of a clerical gentleman,” Commodore Hiram Paulding later wrote. Walker was a small and slender man, with freckles, gray eyes, and thinning hair. “He is said to be remarkable for his abstinence,” Paulding added, “and that wine and the society of ladies have no charm for him.” But these observations did not quite describe Walker during his residence in New Orleans, for there he had a brief relationship with a deaf and mute woman named Ellen Martin. In 1849, she died of cholera, a tragedy that propelled him to San Francisco.

The move turned Walker’s life in a radical new direction. The Gold Rush was in its early stages, attracting tens of thousands to California. The Forty-niners were an independent lot, willing to hazard the long, dangerous journey from the settled states. Duels, gunfights, and brawls erupted regularly.

And there was more to this historical moment than the Gold Rush. Over the previous decade, the United States had expanded deep into Latin American territory, and not always through federal action. Americans in Texas had rebelled against Mexico, established their independence, and won annexation to the United States in 1845. The Mexican War broke out in 1846, leading to the absorption of a third of Mexico—with the assistance of American citizens in California, who staged their own revolt against Mexico.

Enthusiasm for geographical growth came to be known by the newspaper slogan of “manifest destiny,” but it reflected mixed motives. Some Southerners hoped to extend the territory open to slavery. Others felt an evangelical fervor for exporting democracy and Protestantism to the military regimes of Catholic Latin America.

This aggressive expansionism gave rise to a strange phenomenon known as filibustering. Filibusters were independent adventurers who launched freelance invasions of foreign countries, usually aiming to annex them to the United States. The decade before the Civil War saw the great flowering of filibustering. In 1850 and 1851, for example, scores of Americans landed in Cuba in disastrous forays.

The restless Walker decided to become the greatest filibuster of them all. In 1853, he invaded Mexico with a handful of men, and barely escaped alive. The United States government tried him for violating the neutrality act, which prohibited private citizens from warring against foreign nations. But a jury in turbulent San Francisco swiftly exonerated him, turning his failure into a personal (if not military) triumph.

In 1855, he found his next target: Nicaragua. But this time his expedition would be conducted in cooperation with local forces. In its less than two decades of full independence, Nicaragua had suffered from repeated civil wars, waged by the leaders of its two main cities, León and Granada—capitals respectively of the Liberal and Conservative Parties. When the Liberals rose in yet another revolt, Byron Cole, a friend of Walker’s, negotiated a contract for Walker to fight on their side.

Why did Walker care about poor and distant Nicaragua? It was home to one of the key “transit routes” between California and the rest of the United States. Before the construction of the transcontinental railroad and the Panama Canal, most travel and almost all commerce between the two coasts went by steamship to Central America, where two routes crossed the isthmus. The first was in Panama, spanned by the Panama Railroad. The other was in Nicaragua.

In 1851, Cornelius Vanderbilt (known to all as the Commodore) had established the Accessory Transit Company to span Nicaragua and connect to his steamships. The company ran riverboats from the Atlantic port of Greytown, up the San Juan River to Lake Nicaragua. From the lake’s western shore, a twelve-mile carriage road descended to the Pacific port of San Juan del Sur. Accessory Transit carried tens of thousands of passengers each year, making Nicaragua a strategic priority for the federal government. As President James Buchanan later said, “To the United States these routes are of incalculable importance as a means of communication between their Atlantic and Pacific possessions.”

On May 4, 1855, Walker slipped out of San Francisco Bay in the brig Vesta, along with fifty-seven followers (one of whom died at sea). Though he spoke little Spanish, he demanded an independent command when he arrived in Nicaragua. He promptly launched a blundering attack, and was lucky to survive.

But luck was his foremost attribute. The Liberals’ chief executive and commanding general both died soon after his arrival, making him the senior leader on his side. Then Walker carried out perhaps the only inspired maneuver of his career. He commandeered an Accessory Transit steamboat, landed his men in the rear of Granada, and captured the city. He then took hostage the families of the Conservative leaders.

General Corral quickly agreed to terms. Walker, seeking to consolidate his power in the small country, created a unity provisional government, with the weak Patricio Rivas as president, himself as commander of the army, and Corral as secretary of war. Shortly afterward, Walker put Corral on trial for treason and had him publicly executed. The freckle-faced filibuster had made himself into Nicaragua’s strongman.

He would be hard-pressed to remain in power. The neighboring republics, alarmed by his success, prepared for war. And he could not rely on Nicaraguans to fight for him. As he later wrote, “Internal order as well as freedom from foreign invasion depended . . . entirely on the rapid arrival of some hundreds of Americans.” And that made him dependent upon the steamships of the Accessory Transit Company.

Before leaving San Francisco, he had called upon Cornelius K. Garrison, Accessory Transit’s agent there, to ask for passage for himself and his men. Garrison refused. Later, when an Accessory Transit official in Nicaragua donated $20,000 in company gold to Walker’s regime, Garrison fired him immediately.

But Garrison could not remain aloof forever. One of Walker’s closest friends was about to embroil Garrison, and some of the most prominent businessmen in America, in a private war over Walker’s very survival.

That friend’s name was Edmund Randolph, grandson of a Founding Father and a leading attorney in San Francisco. After Walker’s triumph, Randolph paid a visit to Garrison. He explained that he would soon convince Walker to revoke the charter of the Accessory Transit Company (which was a Nicaraguan corporation). Randolph freely admitted that he wanted “a grant for myself of a charter of a similar nature.” He had no steamships, but no matter; he intended to profit by flipping the transit grant, selling it to Garrison as an individual entrepreneur.

Garrison indignantly refused to take part. His partner, Charles Morgan, was the foremost man in Accessory Transit in New York; he could not afford to betray him, even if he was willing to. But Randolph’s certainty about the company’s demise gave him pause. “If things should take that twine,” Randolph recalled him musing, “he did not wish to be involved in the ruin. . . . He would do nothing whatever against the company, but if they fell wanted to save himself.”

The wily Garrison saw a way to save himself, and Morgan as well. He sent his son to Nicaragua, along with Randolph, to negotiate with Walker over the terms for a new line. Once his son reached an agreement, he was to sail for New York to bring Morgan into the plot before it became public knowledge and Accessory Transit shares collapsed in the stock market.

Walker agreed to Randolph’s plan, and the two soon made a deal with Garrison’s son. Morgan and Garrison would pay Randolph for the transit rights and start a new steamship and transit line. Walker would seize the Accessory Transit riverboats and domestic infrastructure, and give them to the two partners. The new line would carry filibuster recruits from the United States for free, accumulating credits toward the cost of the property in Nicaragua. Garrison’s son rushed to New York to explain the arrangement to Morgan.

As luck would have it, at that very moment Morgan was being pushed out of Accessory Transit by Cornelius Vanderbilt. The two had battled over the company for almost three years; Vanderbilt had departed from its management, but at the end of 1855 he began to buy control of its stock. So Morgan readily agreed to Randolph’s plan, and secretly prepared to start the new Nicaragua line.

News of Walker’s revocation of the Accessory Transit charter hit Wall Street like a “bombshell,” the press reported. Vanderbilt rushed to Washington to secure federal aid, but the Cabinet, like the nation itself, was divided over whether Walker was a criminal or a hero. So the Commodore sent a subordinate to retake the company’s steamboats on the San Juan River. He counted on support from the British, who were hostile to filibustering and claimed a protectorate over the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua. The Royal Navy stationed warships in the harbor of Greytown, the little port at the mouth of the San Juan.

But the former Accessory Transit agent in charge of the boats refused to hand over them over, and the British declined to intervene. It was a fateful failure. Had Vanderbilt’s man succeeded, Morgan and Garrison could not have opened their line, and Walker would have been cut off. Instead, Central America descended into war.

In April 1856, Costa Rica launched an invasion of Nicaragua, occupying the city of Rivas. Walker launched a typical frontal assault and was soundly defeated. But his luck held: a cholera outbreak forced the Costa Ricans to retreat, even as Walker gained hundreds of recruits carried by Garrison and Morgan’s new line.

But Walker’s arrogance alienated even his own puppet president, Patricio Rivas, who suddenly denounced him as an usurper and fled over the border. A northern alliance, consisting of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, marched into Nicaragua, occupying León on July 12. Walker responded by staging a rigged election that made him president. He declared English to be the official language, and issued an edict legalizing slavery. Then the Costa Ricans invaded again from the south.

Walker knew he could survive only if he kept open the flow of reinforcements from the United States. As he later wrote, “It was all-important to keep the transit clear.” So he decided to withdraw to the south and garrison the transit route, from Rivas in the west to forts along the San Juan River. He evacuated Granada, leaving a detachment with orders to burn the city to the ground. When the filibusters finished, they erected a sign that read, “Aqui fue Granada”—“Here was Granada.”

By the end of 1856, Walker felt reassured. “Walker, keeping his forces concentrated, can maintain himself in Rivas,” an American naval officer reported. “If the external aids he has hitherto relied upon do not fail him, he will repel his enemies.”

At that moment, Vanderbilt was moving to cut Walker off from his “external aids.” Walker’s greatest vulnerability, he believed, remained the steamboats on the San Juan River. If Vanderbilt’s agents could seize them, he would force Garrison and Morgan to halt operations and cut off Walker’s flow of reinforcements. This time he negotiated an alliance with Costa Rica. In October 1856, he dispatched a special agent to San José, the Costa Rican capital. The agent, a New Yorker named Sylvanus Spencer, had worked on the San Juan River, which gave him precious knowledge of the steamboat operations.

Spencer arrived in San José with Vanderbilt’s plan of attack and $40,000 in gold to pay Costa Rica’s expenses. President Juan Rafael Mora put him in charge of a commando force. Spencer led the men through the rain forest to the San Juan River, where they captured a filibuster strongpoint and a few steamboats. Then he used his knowledge to bloodlessly seize the rest of the boats and forts—sailing up in a captured steamer, giving the right signals, then surprising the filibusters with soldiers who had been hiding on deck. Within days, Spencer controlled the river. Morgan and Garrison, unable to send passengers and reinforcements across Nicaragua, immediately withdrew their ships. Walker was isolated.

Walker withdrew into Rivas, where the Central American alliance besieged him for months. Finally, on May 1, 1857, he surrendered to an American naval officer, who conducted him and his men out of the country.

In some respects, Vanderbilt’s victory was hollow. Though he inflicted heavy financial losses on Garrison and Morgan, he failed to reopen the transit route. The Nicaraguans could not bring themselves to allow large numbers of North Americans into the country again, lest they face Walker once more.

“That man has done more injury to the commercial & political interests of the United States than any man living,” wrote President Buchanan. But the federal government proved ineffectual in either convicting Walker in court, or in preventing further expeditions. Wherever Walker went in the United States, he was greeted by throngs of admirers.

And so he tried again, and again. On November 25, 1857, he landed at Greytown with 270 followers; in a controversial move, the US Navy forced his prompt surrender. Walker launched a final invasion in 1860. But now his luck ran out. The Royal Navy captured him, then handed him over to the nearest authorities, the Hondurans. On September 12, 1860, Walker faced his own firing squad.

Within a year, the United States plunged into the Civil War. Places with names like Antietam, Shiloh, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness soon obscured Granada, Rivas, and Greytown in the American imagination. Memories of the filibuster faded. But Walker himself had contributed to—or reflected—the nation’s descent into war. He had emerged out of a rising tide of freelance violence; and he had appealed to Southern hopes for expanding slavery by reinstituting it in Nicaragua.

Though he has been largely forgotten in the United States, he is still remembered by Central Americans, who see him as a symbol of imperialism. The fight to eject Walker forms part of Nicaragua’s national legend, a critical period in the formation of its national identity.

If nothing else, his disruption of a critical route to California, his military dictatorship, and his ruthless violence—particularly his wanton destruction of Grenada, one of the oldest cities in the western hemisphere—prove that he was one of the most dangerous international criminals of the nineteenth century, if not all our history.

T. J. Stiles is the author of The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (2009), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, and Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War (2002).

No comments:

Post a Comment