Now the arrogance of the white man is something to behold. Here a nation that has existed for well over a thosand years and has tomes of wisdom the white man has used for the few hundreds of years they've been an un-Godly world power gonna' tell people who practically invented government they don't know what they're doing! Now that's arrogance for you! Here it is a people who are the masters of disenfranchisement, government corruption, and satanic evil gonna try to preach to a nation that goes back farther than they ever will! You wanna talk about somebody's wrong, why did you kill all the people on the island of Tasmania? Not a single native Tasmanian (Black people) is alive today! Why are you still in Africa, destroying crops, stealing oil and diamonds, trying to build mercenary armies to start wars there? Why don't you talk about the white police in the U.S, murdering black children and not going to jail for it? As the Lord said you need to remove the log from your own eyes before you try to remove the speck from somebody else's eye!

As China becomes, again, the world's largest economy, it wants

the respect it enjoyed in centuries past. But it does not know how to

achieve or deserve it

MATTHEW BOULTON, James Watt’s partner in the development of the

steam engine and one of the 18th century’s greatest industrialists, was

in no doubt about the importance of Britain’s first embassy to the court

of the Chinese emperor. “I conceive”, he wrote to James Cobb, secretary

of the East India Company, “the present occasion to be the most

favourable that ever occurred for the introduction of our manufactures

into the most extensive market in the world.”

In light of this great opportunity, he argued, George Macartney’s 1793 mission to Beijing should take a “very extensive selection of specimens of all the articles we make both for ornament and use.” By displaying such a selection to the emperor, court and people, Macartney’s embassy would learn what the Chinese wanted. Boulton’s Birmingham factories, along with those of his friends in other industries, would then set about producing those desiderata in unheard-of bulk, to everybody’s benefit.

That is not how things turned out. The emperor accepted Macartney’s gifts, and quite liked some of them—a model of the Royal Sovereign, a first-rate man o’ war, seemed particularly to catch his fancy—but understood the whole transaction as one of tribute, not trade. The court saw a visit from the representatives of King George as something similar in kind to the opportunities the emperor’s Ministry of Rituals provided for envoys from Korea and Vietnam to express their respect and devotion to the Ruler of All Under Heaven. (Dealings with the less sophisticated foreigners from inner Asia were the responsibility of the Office of Barbarian Affairs.)

The emperor was thus having none of Macartney’s scandalous suggestion that the Son of Heaven and King George should be perceived as equals. He professed himself happy that Britain’s tribute, though admittedly commonplace, should have come from supplicants so far away. But he did not see it as the beginning of a new trading relationship: “We have never valued ingenious articles, nor do we have the slightest need of your country’s manufactures…Curios and the boasted ingenuity of their devices I prize not.” Macartney’s request that more ports in China be opened to trade (the East India Company was limited to Guangzhou, then known as Canton) and that a warehouse be set up in Beijing itself was flatly refused. China at that time did not reject the outside world, as Japan did. It was engaged with barbarians on all fronts. It just failed to see that they had very much to offer.

In retrospect, a more active interest in extramural matters might have been advisable. China was unaware that an economic, technological and cultural revolution was taking place in Europe and being felt throughout the rest of the world. The subsequent rise of colonialist capitalism would prove the greatest challenge it would ever face. The Chinese empire Macartney visited had been (a few periods of collapse and invasion notwithstanding) the planet’s most populous political entity and richest economy for most of two millennia. In the following two centuries all of that would be reversed. China would be semi-colonised, humiliated, pauperised and torn by civil war and revolution.

Now, though, the country has become what Macartney was looking for: a relatively open market that very much wants to trade. To appropriate Boulton, the past two decades have seen the most favourable conditions that have ever occurred for the introduction of China’s manufactures into the most extensive markets in the world. That has brought China remarkable prosperity. In terms of purchasing power it is poised to retake its place as the biggest economy in the world. Still home to hundreds of millions mired in poverty, it is also a 21st-century nation of Norman Foster airports and shining solar farms. It has rolled a rover across the face of the moon, and it hopes to send people to follow it.

And

now it is a nation that wants some things very much. In general, it

knows what these things are. At home its people want continued growth,

its leaders the stability that growth can buy. On the international

stage people and Communist Party want a new deference and the influence

that befits their nation’s stature. Thus China wants the current

dispensation to stay the same—it wants the conditions that have helped

it grow to endure—but at the same time it wants it turned into something

else.

And

now it is a nation that wants some things very much. In general, it

knows what these things are. At home its people want continued growth,

its leaders the stability that growth can buy. On the international

stage people and Communist Party want a new deference and the influence

that befits their nation’s stature. Thus China wants the current

dispensation to stay the same—it wants the conditions that have helped

it grow to endure—but at the same time it wants it turned into something

else.

Finessing this need for things to change yet stay the same would be a tricky task in any circumstances. It is made harder by the fact that China’s Leninist leadership is already managing a huge contradiction between change and stasis at home as it tries to keep its grip on a society which has transformed itself socially almost as fast as it has grown economically. And it is made more dangerous by the fact that China is steeped in a belligerent form of nationalism and ruled over by men who respond to every perceived threat and slight with disproportionate self-assertion.

The post-perestroika collapse of the Soviet Union taught China’s leaders not just the dangers of political reform but also a profound distrust of America: would it undermine them next? Xi Jinping, the president, has since been spooked by the chaos unleashed in the Arab spring. It seems he wants to try to cleanse the party from within so it can continue to rule while refusing any notions of political plurality or an independent judiciary. That consolidation is influencing China’s foreign policy.

China is building airstrips on disputed islands in the South China Sea, moving oil rigs into disputed waters and redefining its airspace without any clear programme for turning such assertion into the acknowledged status it sees as its due. This troubles its neighbours, and it troubles America. Put together China’s desire to re-establish itself (without being fully clear about what that might entail) and America’s determination not to let that desire disrupt its interests and those of its allies (without being clear about how to respond) and you have the sort of ill-defined rivalry that can be very dangerous indeed. Shi Yinhong, of Renmin University in Beijing, one of China’s most eminent foreign-policy commentators, says that, five years ago, he was sure that China could rise peacefully, as it says it wants to. Now, he says, he is not so sure.

In light of this great opportunity, he argued, George Macartney’s 1793 mission to Beijing should take a “very extensive selection of specimens of all the articles we make both for ornament and use.” By displaying such a selection to the emperor, court and people, Macartney’s embassy would learn what the Chinese wanted. Boulton’s Birmingham factories, along with those of his friends in other industries, would then set about producing those desiderata in unheard-of bulk, to everybody’s benefit.

That is not how things turned out. The emperor accepted Macartney’s gifts, and quite liked some of them—a model of the Royal Sovereign, a first-rate man o’ war, seemed particularly to catch his fancy—but understood the whole transaction as one of tribute, not trade. The court saw a visit from the representatives of King George as something similar in kind to the opportunities the emperor’s Ministry of Rituals provided for envoys from Korea and Vietnam to express their respect and devotion to the Ruler of All Under Heaven. (Dealings with the less sophisticated foreigners from inner Asia were the responsibility of the Office of Barbarian Affairs.)

The emperor was thus having none of Macartney’s scandalous suggestion that the Son of Heaven and King George should be perceived as equals. He professed himself happy that Britain’s tribute, though admittedly commonplace, should have come from supplicants so far away. But he did not see it as the beginning of a new trading relationship: “We have never valued ingenious articles, nor do we have the slightest need of your country’s manufactures…Curios and the boasted ingenuity of their devices I prize not.” Macartney’s request that more ports in China be opened to trade (the East India Company was limited to Guangzhou, then known as Canton) and that a warehouse be set up in Beijing itself was flatly refused. China at that time did not reject the outside world, as Japan did. It was engaged with barbarians on all fronts. It just failed to see that they had very much to offer.

In retrospect, a more active interest in extramural matters might have been advisable. China was unaware that an economic, technological and cultural revolution was taking place in Europe and being felt throughout the rest of the world. The subsequent rise of colonialist capitalism would prove the greatest challenge it would ever face. The Chinese empire Macartney visited had been (a few periods of collapse and invasion notwithstanding) the planet’s most populous political entity and richest economy for most of two millennia. In the following two centuries all of that would be reversed. China would be semi-colonised, humiliated, pauperised and torn by civil war and revolution.

Now, though, the country has become what Macartney was looking for: a relatively open market that very much wants to trade. To appropriate Boulton, the past two decades have seen the most favourable conditions that have ever occurred for the introduction of China’s manufactures into the most extensive markets in the world. That has brought China remarkable prosperity. In terms of purchasing power it is poised to retake its place as the biggest economy in the world. Still home to hundreds of millions mired in poverty, it is also a 21st-century nation of Norman Foster airports and shining solar farms. It has rolled a rover across the face of the moon, and it hopes to send people to follow it.

Video

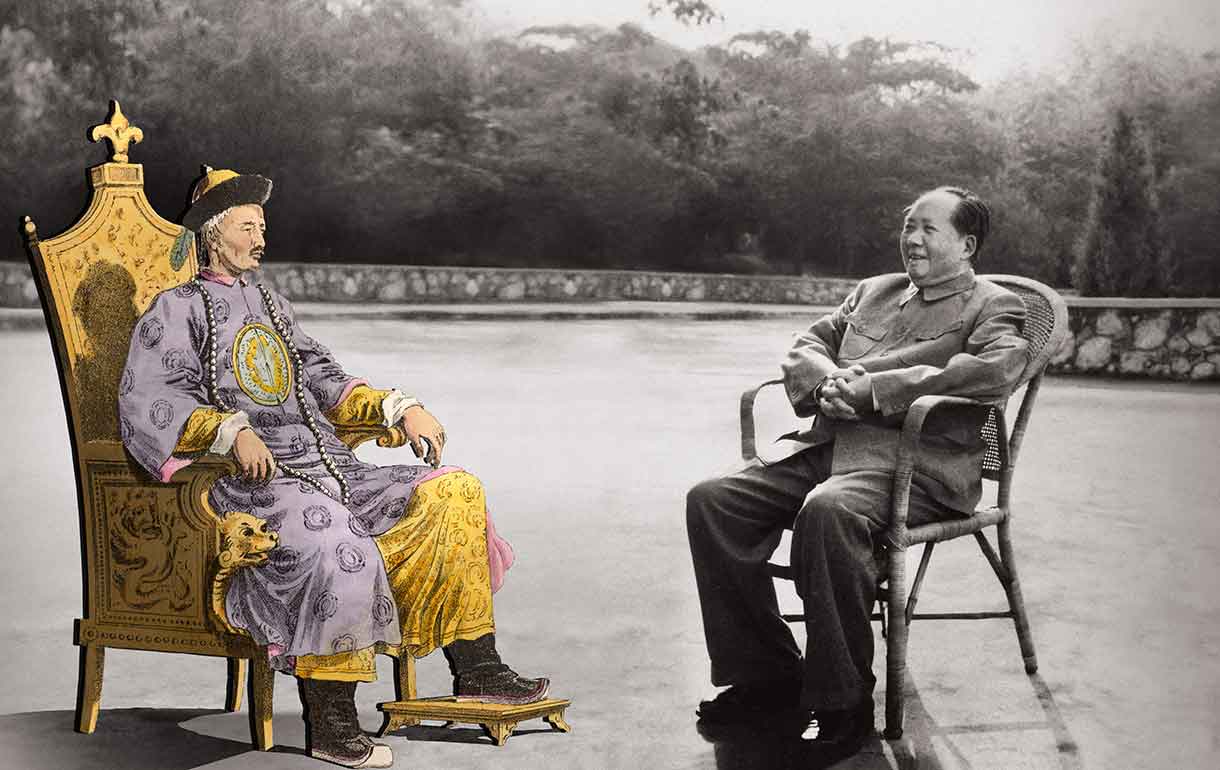

An embassy to China

Finessing this need for things to change yet stay the same would be a tricky task in any circumstances. It is made harder by the fact that China’s Leninist leadership is already managing a huge contradiction between change and stasis at home as it tries to keep its grip on a society which has transformed itself socially almost as fast as it has grown economically. And it is made more dangerous by the fact that China is steeped in a belligerent form of nationalism and ruled over by men who respond to every perceived threat and slight with disproportionate self-assertion.

The post-perestroika collapse of the Soviet Union taught China’s leaders not just the dangers of political reform but also a profound distrust of America: would it undermine them next? Xi Jinping, the president, has since been spooked by the chaos unleashed in the Arab spring. It seems he wants to try to cleanse the party from within so it can continue to rule while refusing any notions of political plurality or an independent judiciary. That consolidation is influencing China’s foreign policy.

China is building airstrips on disputed islands in the South China Sea, moving oil rigs into disputed waters and redefining its airspace without any clear programme for turning such assertion into the acknowledged status it sees as its due. This troubles its neighbours, and it troubles America. Put together China’s desire to re-establish itself (without being fully clear about what that might entail) and America’s determination not to let that desire disrupt its interests and those of its allies (without being clear about how to respond) and you have the sort of ill-defined rivalry that can be very dangerous indeed. Shi Yinhong, of Renmin University in Beijing, one of China’s most eminent foreign-policy commentators, says that, five years ago, he was sure that China could rise peacefully, as it says it wants to. Now, he says, he is not so sure.

WHEN China was first unified in 221BC, Rome was

fighting Carthage for dominion over the western Mediterranean. Rome

would go on to rise further and, famously, fall. China collapsed, too,

many times, but the model had been set that it must always reunite. By

the end of the Han dynasty in 220AD its rulers had institutionalised the

teachings of Confucius, which emphasised the value of social hierarchy

and personal morality, as the basis for government. By the Tang dynasty

in the 7th century—at about the time Muhammad returned to Mecca—China

was one of the wealthiest and most illustrious civilisations on Earth.

Its economic and military power dwarfed that of neighbouring peoples.

Its cultural riches and Confucian moral order made that pre-eminence

seem natural to all concerned. China was the model to emulate. Kyoto in

Japan is laid out like 8th-century Chang’an (modern day Xi’an). The

Koreans and Vietnamese adopted Chinese script. Confucian teaching

became, and remains, the philosophical foundation of many Asian

cultures. Just as it was right for the emperor to occupy the apex of

China’s hierarchy, so it was meet for China to sit atop the world’s.

Macartney

came to this paragon at the height of its Qing dynasty. In the middle

of the 18th century the emperor had brought Tibet and Turkestan into the

empire by means of intensive military campaigns and the genocidal

elimination of the Dzungars, taking it to its greatest historical

extent. Though everyday life for the peasants was grim, imperial life

was magnificent. But for all the wealth and despite—or perhaps because

of—his imperious dismissal, Macartney felt the state was not as

sempiternal as its rulers would have it. It was, he wrote, a “crazy,

first rate man o’ war”, able to overawe her neighbours “merely by her

bulk and appearance”. He sensed something of its fragility and the

problems to come. “She may drift sometime as a wreck and then be dashed

to pieces on the shore.”

The

structural reasons for China’s subsequent decline and the empire’s

demise have been much discussed. Some point to what Mark Elvin, a

historian, calls “the high-level equilibrium trap”; the country ran well

enough, with cheap labour and efficient administration, that supply and

demand could be easily matched in a way that left no incentive to

invest in technological improvement. Others note that Europe benefited

from competition and trade between states, which drove its capacity for

weaponry and its appetites for new markets. As Kenneth Pomeranz, an

American historian, has argued, access to cheap commodities from the

Americas was a factor in driving industrialisation in Britain and Europe

that China did not enjoy. So was the good luck of having coal deposits

close to Europe’s centres of industry; China’s coal and its factories

were separated by thousands of kilometres, a problem that remains trying

today.

No comments:

Post a Comment